At this point in the meltdown timeline, municipal bond defaults have not yet occurred in the traditional sectors we think about such as cities, towns, states, utility systems and school districts. The few notable exceptions include Vallejo, California, currently working through a Chapter 9 bankruptcy and Jefferson County, Alabama sewer system, which is a heavily leveraged enterprise working through its reserves and under its sixth? tenth? forebearance agreement with a number of swap providers, so according to some balance sheets not yet really in default. Which brings me to this blog topic: what, after all, is a default?

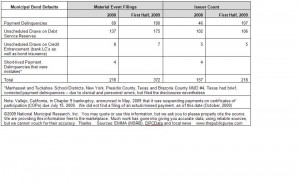

The SEC currently requires disclosure of a list of material events, so some default reports include a draw on cash reserves along with payment defaults in the same statistics. The typical understanding of default is a non-payment to the investor or bondholder. When a security is spiraling downhill fast, a cash draw frequently ripens into a payment default. Both will be noted in the material event filings. The numbers will also include multiple filings for different series of bonds for the same issuer, or for two missed payments in the same year, or for multiple missed payments on a monthly basis.

When an investor or portfolio manager, or bond insurer or rating agency makes a decision about the quality of a security, they are usually thinking about the credit, meaning the borrower, or in some cases the obligor if it’s different than the borrower – that is, which entity has to pay back the obligation. So if you don’t like an obligor, you are not going to like Series 2006A from that obligor as well as not liking Series 2007B.

To clear this up, we parsed the default filings for 2008 and the first half of 2009 for reserve draws, payment defaults and unique obligors vs. actual filings. If you click on the attached chart, you can enlarge it. We will be updating this information for third quarter in the near future, so stay tuned….

“The typical understanding of default is a non-payment to the investor or bondholder.”

Thank you for making this distinction, many people are much less exact when they discuss defaults in this sector.