Wherein we dive into the paradigm shift in higher education funding

Enrollment in post-secondary educational institutions peaked in 1980 and has declined since then. In the recovery following the Great Recession, enrollment grew modestly but declined steadily from 2010, according to the National Center for Educational Statistics. In the survey we discussed in Part One, 50% of those queried were concerned about graduating with high levels of debt. Evolution of higher education in the U.S. has alternated between pre-Civil War private liberal arts to public land-grant institutions in the states (Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890), primarily viewed as a “public good”, to promote economic development through agriculture, applied sciences and engineering. In 1980, post-secondary education reverted to public/private funding as states shifted costs to students and their families (update here). We dive into the issue of student loans, the cost of higher education and the overlap with homeownership and wealth-building.

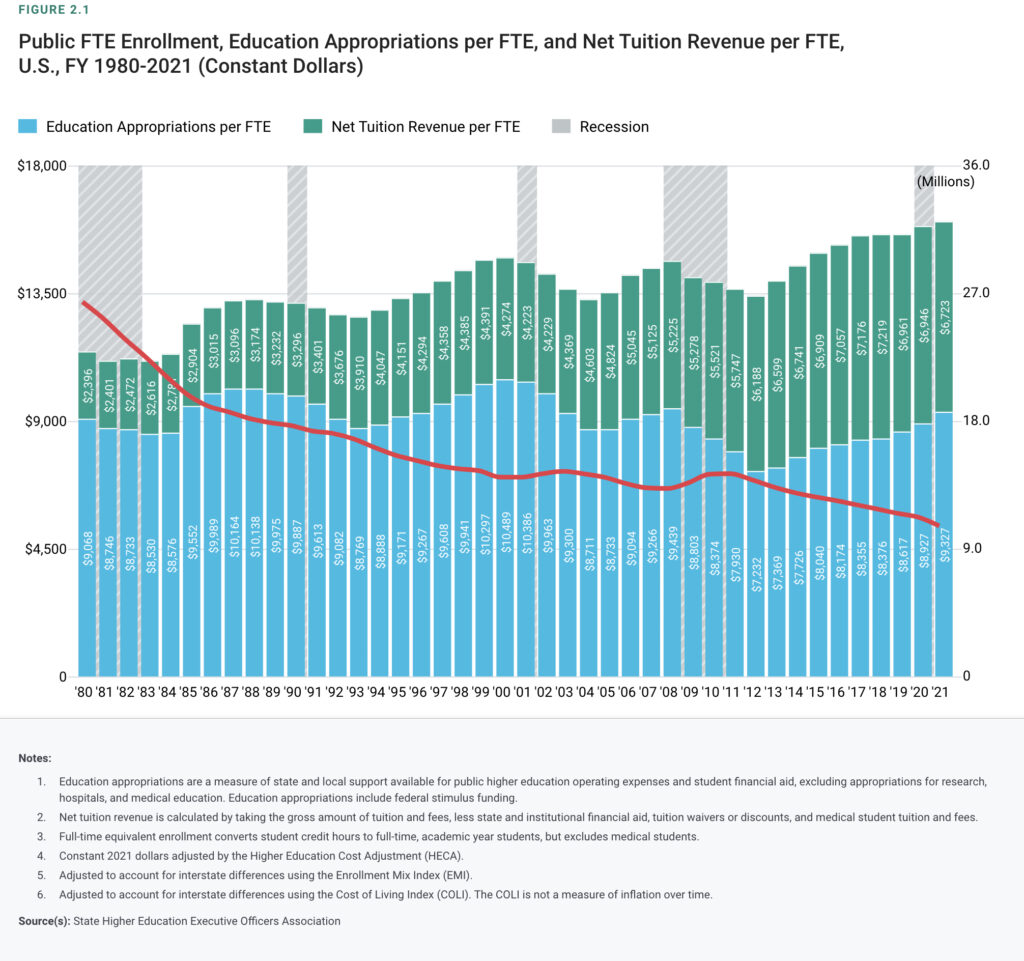

For visual context, the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, SHEEO, shows enrollment decline (right scale) and the share of cost born by tuition compared with the share of state (and local) appropriations from 1980-2021 (in constant dollars and for public higher education, full-time equivalent, FTE, left scale). SHEEO dubs this their “wave” chart, since tuition as a proportion of total cost tends to grow after each recession (grey bars), as state and local governments reduce appropriations and fall back (in constant dollars) during recovery periods. State/local appropriations did grow following a nadir in 2012, but has never reached the proportion seen in the late 1980’s or 1990’s. Stated differently, states and lenders reached increasingly into student and family “wallets” over this time. In prior generations, the first decade or two following post-secondary graduations have been a time for many to save for a down payment on a home. More recently, paying off student debt has replaced such savings.

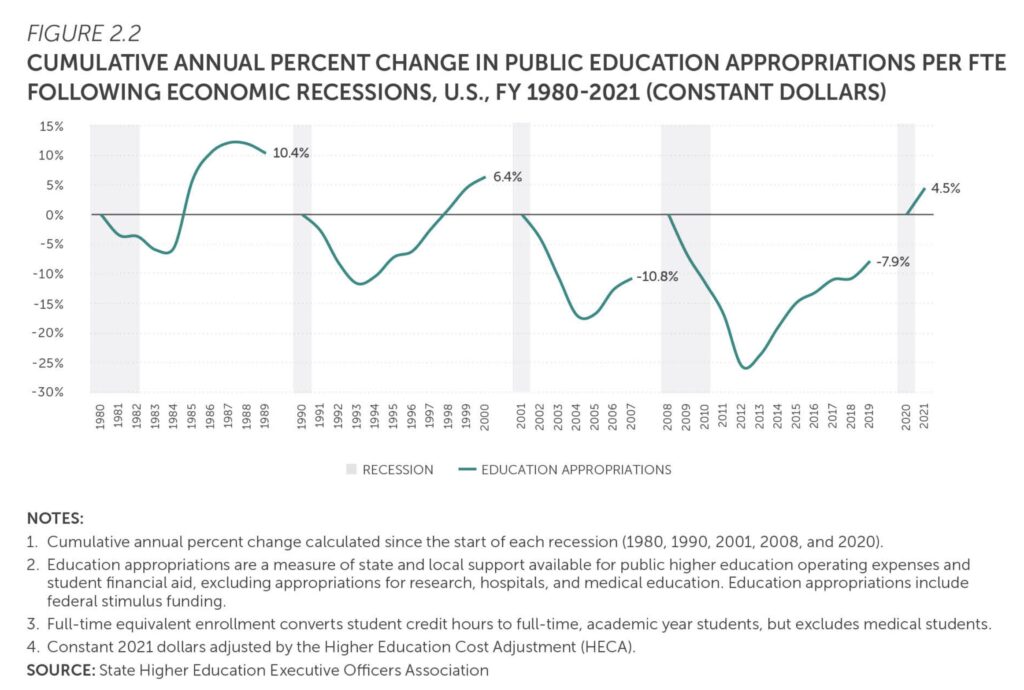

Shown differently, SHEEO captured the percent change in appropriations for public education (in constant dollars, per FTE) following economic recessions in the following chart. The Bureau of Labor Statistics, as part of their consumer price index, commented (in 2016) that college tuition and fees increased 63% between January 2006-2016.

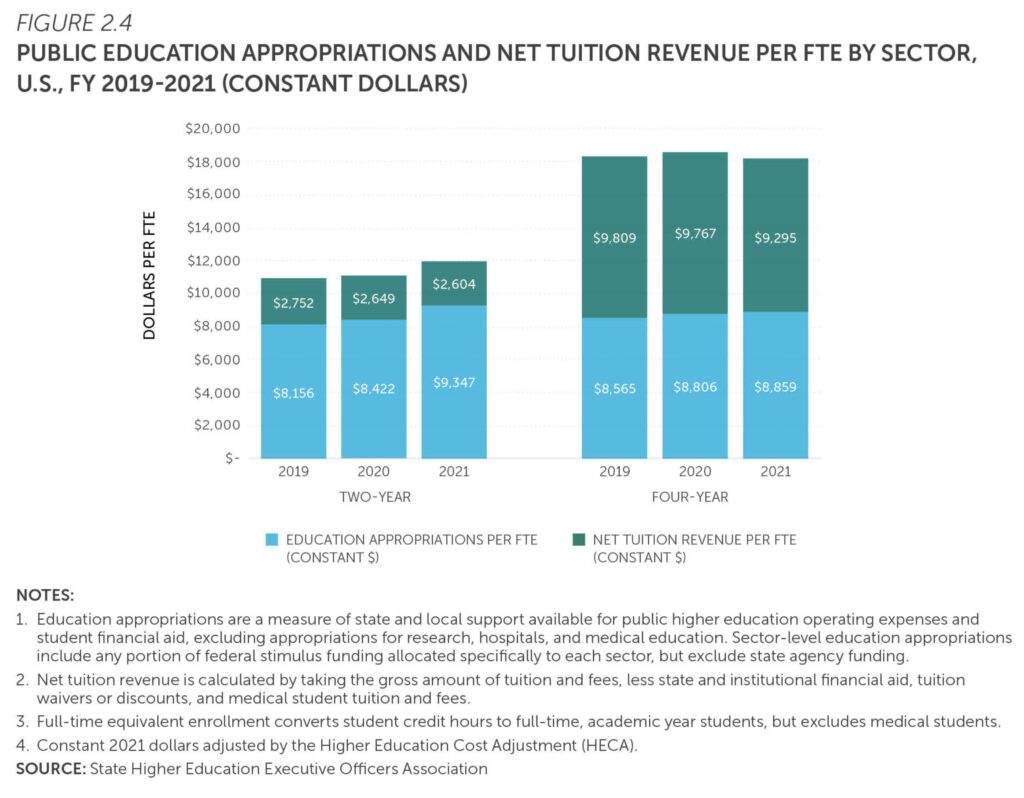

However, to get a better picture of the impact of student debt, it is important to parse these figures further. For example, tuition/state appropriations are much lower for two-year institutions and much higher for four-year institutions – again showing SHEEO data here:

Disaggregating the numbers by race tells a significantly different story. Enrollment in higher education jumped in 2010, and especially by black and African American students. This coincided with the time when higher education debt surpassed credit cards, auto loans and home equity borrowing. As Jill Barshay pointed out in her article in the Hechinger Report, unemployment was high following the Great Recession and much of the increase “was driven by older adults”, also dubbed “non-traditional students”. In 2009, “the 2009 Recovery Act increased the amount of Pell Grants to low-income students to more than $5000 per year” and widened eligibility, according to Barshay’s reporting. Legislation also raised the amounts students could borrow in 2007 and 2008, helping along the replacement of declining state aid with debt.

The current administration’s student debt reprieve is slated for elimination in Speaker McCarthy’s House budget. The reprieve was put into place because of COVID, and extension of the payment pause is under litigation in front of the Supreme Court. Currently the pause “is extended until the U.S. Department of Education is permitted to implement the Debt Relief program or the litigation is resolved. Payments will restart 60 days later.” You can read further here. The litigation turns on whether the Secretary of Education has the authority to cancel the debt (up to $10,000 or $20,000 for those who received a Pell grant). Another case turns on whether forgiveness would harm states. For example, the Missouri Higher Education Loan Authority (MOHELA), a third-party loan servicer, has an obligation to contribute to state university funds. Even though MOHELA hasn’t contributed for about 15 years, the suit argues that having fewer students with debt will harm the state of Missouri. A strange argument, it seems, but we will see a decision before the court’s current term ends in June. (See the Brookings explainer here.)

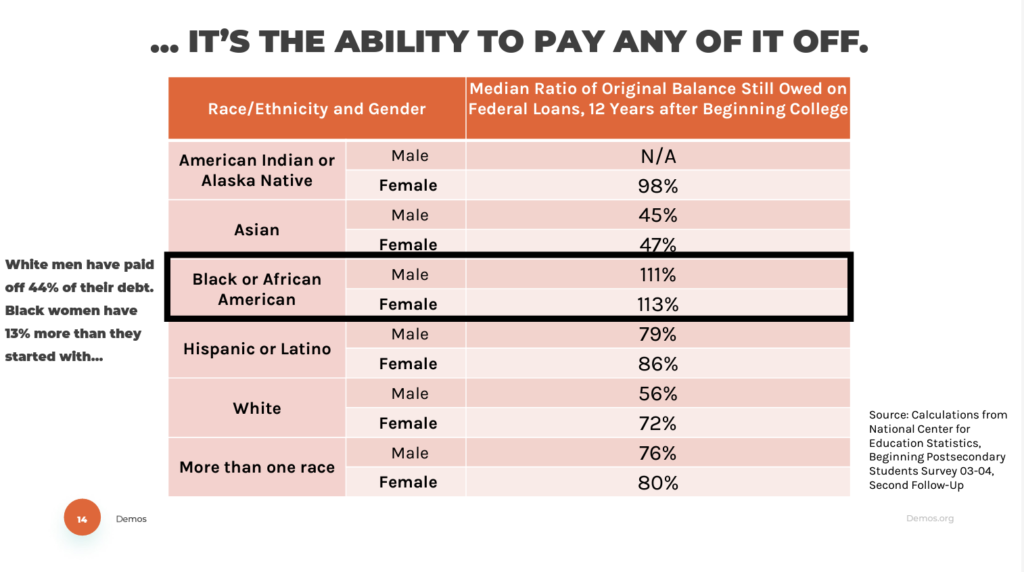

Policy issues are not part of the court’s discussion, but the decision will certainly have economic and policy implications. The Education Trust cites 8.5 million black borrowers with an average of $53,000 in debt balances. Studies have shown the value of higher education for higher earnings in life and ultimately higher net worth. However only a handful of studies disaggregate the statistics by race, where there is significant divergence in results. Demos, an organization that considers themselves a “think and do tank”, studied student debt in the context of racial wealth gaps. Their PowerPoint showed median net worth for white graduates with a bachelor’s degree or higher, at $399,000, while Black households had median net worth of $68,200. (This data was sourced from the Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances and the Demos report dates from 2020.)

The Demos report also shows the balances still owed by race and gender, 12 years after beginning college. White males had paid off 44% of their debt while black women had 13% more debt than when they started. These figures were compiled pre-COVID and pre-repayment suspension.

The connection between a heavy student debt load and the ability to own a home is repeated in the literature. The Urban Institute connects student debt and homeownership here. The National Education Association, NEA, a large teachers’ union profiled a few teachers that they helped get student loan relief through the existing federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program. Several cited the ability to purchase a home once there was some relief from student debt. Krista Detloff, a high school teacher in Minnesota, has been paying off her debt for 25 years. As she stated here, it hampered her family from buying a home and a second car. “Now, since I got my master’s degree in 2015, I still owe $38,000. I’m 48 years old and I’m going to have this debt into retirement.” New Jersey music teacher Sean Ichiro Manes had made more than 120 on-time loan payments over 10 years but continues to pay $700/month on his student loans. He lived with his mother and worked second and third jobs. Finally, two years ago at 42, he was able to afford a mortgage on a condo. In another example, a science teacher has been paying student loans for nearly 40 years and still owes $90,000. “A few years ago, she finally bought a home – but 50 minutes away from her classroom in a more affordable community.”

The company Trulia, a subsidiary of Zillow, has listed housing along with municipalities that are offering financial help with student loan payments. (See Part Four.)

Consumer Debt

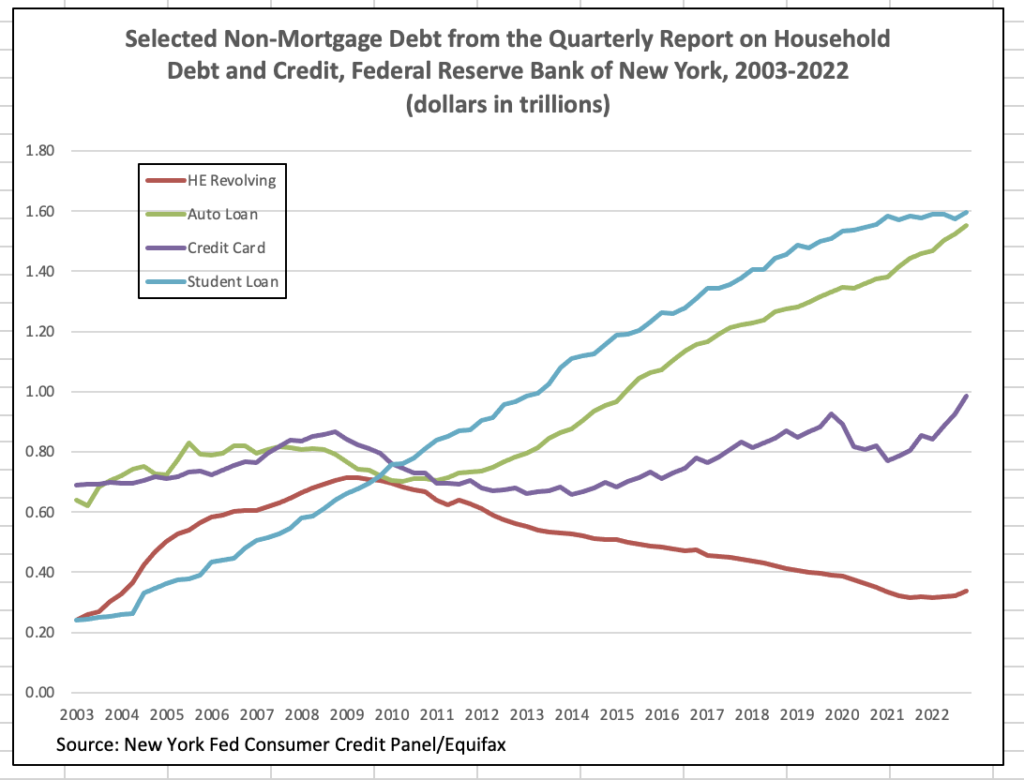

Student debt outstanding passed other forms of consumer debt in 2010: credit card debt, auto loans and home equity loans according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY) and reflected in the chart below. (We omit mortgage balances, mainly for issues of scale). At the peak of the Great Recession the federal government raised the amount that students could borrow in 2007-2008. In addition, the 2009 Recovery Act increased the amount of Pell grants (which are awarded to low-income students) and expanded the number of students that would be eligible. Student loan debt soared and continued to do so through 2022. (The tapering of student debt in 2022 includes the payment suspension granted as temporary emergency financial relief during the pandemic, so debt levels will jump up again in 2023).

- Mortgage balances are the largest form of household debt and grew to $11.9 trillion in Q4 2022. Smaller but consequential, student loan balances reached $1.6 trillion followed by auto loans at $1.55 trillion and credit card balances reached $986 billion. Credit card debt grew significantly during the pandemic (which benefitted state and local sales tax revenues).

Delinquencies are beginning to rise, especially since COVID programs have come to an end. The FRBNY’s commentary “Younger Borrowers Are Struggling with Credit Card and Auto Loan Payments” highlights growth in the 90 day past due delinquencies by age group.

Yes, student loan forgiveness is a controversial and costly proposition. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates that all in, the various forgiveness programs total $970 billion over ten years. However, the Committee also estimated, back in 2016, that the Trump administration’s tax cuts cost the U.S. government about $1 trillion over ten years.

However, creating pipelines that will produce the next generation of talent, particularly where there are critical labor needs, begs for a solution to the high cost of post-secondary education and training. According to Melanie Hanson for the Education Data Initiative, cancelling student loan debt could add $109 billion to annual GDP for the next six years. See “Effects of Cancelling Student Loan Debt” found here. Other takeaways from this report include:

- Current debt cancellation plans “would reduce the debt burden for 35 million Americans” and lift up to 5.2 million households out of poverty.

- Concerning law school debt, 39% of indebted lawyers have postponed or decided not to have children due to their law school debt.

- “Black or African American law school graduates loan debts are 97% higher on average than white law school graduates…”.

- Concerning medical school debt statistics, 73% of medical graduates have educational debt; the average owed is $350,990. Over the last 30 years, the level of debt owed by medical school graduates increased 1561%. The report stated: “of those with more than $200,000 in student debt, 91% of black medical students have such debt, compared with 71% among white students.”

- Elsewhere, an Insider story details one black woman’s law school financial situation. Her student debt precludes saving for retirement. While the Consumer Finance Protection Board (CFPB) recommends that 10% of one’s gross income be put toward paying off federal student loans it would be impossible for the average lawyer to ever pay off their federal student loans at this rate. According to the American Bar Association, women and minority law school graduates bear an inordinate percentage of student debt, much of it due to income disparities.

The dramatic privatization of post-secondary education costs since 1980 reflect a change in U.S. political (and popular) thinking. Will Bunch, who wrote After the Ivory Tower Falls, calls the years from the 1940’s-1970’s the “golden age of college”. After the Great Depression and again after World War II, higher education became one part of a tripod of benefits from the federal government, given mainly to white veterans and their families, and intended to spur growth in the U.S. (Higher education, affordable home-ownership and small business start-up grants were three subsidies included in a series of programs at that time such as the GI Bill, Homeowners Loan Corporation, FHA/VA programs). Indeed, post-war U.S. GDP grew dramatically during the 1950’s and 1960’s.

In addition, Soviet Union strength and their launch of Sputnik in 1957 scared U.S. policymakers. Investing in education at the time was considered a “public good”, important for self-defense and for equipping the U.S. with the talent and innovation to win the Cold War. You can find an interesting interview at Pitchfork Economics with Bunch here. As highlighted in U.S. Senate history, “Sputnik Spurs Passage of the National Defense Education Act” in 1958 (signed by President Eisenhower). As the article states, the NDEA “established the legitimacy of federal funding of higher education…”

Higher education is considered so important that many countries offer free or nearly free tuition to their citizens. “Theedadvocate.org” (yes, that’s spelled correctly) mentions 24 countries, mostly economically developed ones, but three in Africa: Morocco, Egypt and Kenya. Eight countries are in Europe, such as Norway, Sweden, Germany, Denmark, Finland, Austria, Greece, and France.

Today the view has shifted to, “why should taxpayers pay for someone else’s education”? In a recent article from Stateline, Richard Vatz, a professor at Towson University in Maryland, told the publication, “There doesn’t seem to be any justification in taking money from the general public for some people to go to college.” He cited data showing that during COVID, of the students who started two-year college in 2020, only 60% were still studying two years later. First, statistics like this during COVID shutdowns may not be representative of outcomes during more normal times. Second, it is likely that the 60% of continuing students would be earning more over the course of their lives than those who never started in the first place. Third, those who never attended post-secondary education will likely need services of all kinds over the rest of their lives from people with advanced training and skills . With limited population growth and an aging population in the U.S., it behooves us to level-up the earning power and net worth of historically marginalized populations, not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because it is economically sound.

While changes at the federal level are unlikely, state and local governments and some corporations are proposing innovative solutions, for workforce development, wealth-building and dealing with the burden of student debt. Some state and local governments are recognizing the need to support education in their upcoming 2024 budgets. The National Association of State Budget Officers, NASBO, outlined governors’ priority budget items for 2024, many of which include proposals for additional funding for education K-12 and higher education. Focus on workforce development programs is also a priority in many states. The Education Commission of the States in collaboration with the National Governors Association also issued a report on 2024 priorities.

We discuss a selection of some of these ideas in Part Four.

[…] In the context of reducing labor shortages, we discuss the headwind of student debt in Part Three. […]